- The UK has pledged $19 billion for the Sizewell C nuclear plant, and the World Bank has lifted its ban on nuclear funding in developing nations.

- This pivot marks a major policy shift toward embracing nuclear energy as demand for clean, reliable power grows.

- Nuclear is gaining support as the only scalable, emission-free baseload option, with over 30 countries pledging to triple nuclear capacity by 2050.

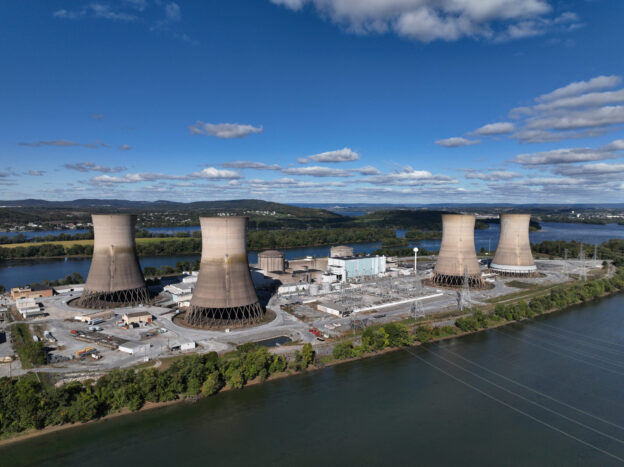

The nuclear power industry has been enjoying the spotlight lately. In just the past two days, the UK pledged $19 billion in additional funding for a nuclear project, and the World Bank lifted a ban on nuclear financing in developing nations, in place since 2017. A nuclear age is coming.

“We need new nuclear to deliver a golden age of clean energy abundance, because that is the only way to protect family finances, take back control of our energy, and tackle the climate crisis,” UK energy minister Ed Miliband said in a statement in comments on the news that the Keir Starmer government would invest the equivalent of $19.3 billion in the construction of the Sizewell C nuclear power plant.

“We will support efforts to extend the life of existing reactors in countries that already have them, and help support grid upgrades and related infrastructure,” the president of the World Bank, Ajay Banga, said in an email to staff, as quoted by the Financial Times. “We will also work to accelerate the potential of small modular reactors – so they can become a viable option for more countries over time.”

In separate nuclear news, a German fusion startup raised a record amount of money, at 130 million euros, for its effort to bring the technology to market. It may not seem like a lot, but the company, Proxima, started with a funding round of just 7 million euros, so this latest round shows a definite spike in interest. Its pitch: building an alternative to the tokamak that other fusion developers use, called the stellarator, which it believes would make fusion commercial.

What all these developments have in common is the recognition that the world will be needing a lot more electricity in the not-too-distant future, especially the developing world. Indeed, the World Bank expects electricity demand in developing countries to increase twofold over just the next decade. This is good news because it means more people are going to be able to afford a consistent electricity supply. It is, at the same time, challenging because this electricity has to come from somewhere, and the World Bank is still not sure it wants to resume funding gas-fired generation. Nuclear, on the other hand? That’s all right. It’s emission-free. It is also baseload.

Building more nuclear-and extending the life of existing reactors-is part of the latest round of COP pledges, made at the latest edition of the gathering, last year. There, more than 30 signatories agreed to triple the world’s nuclear power generation capacity by 2050 as part of efforts to meet their Paris Agreement promises of a net-zero economy. It was an important acknowledgment that, despite years of campaigning, the wind and solar lobby could not convince everyone that wind and solar can handle the grid on their own-because they clearly can’t. And this makes nuclear the only comparable alternative if the level of carbon dioxide emissions remains a top priority.

Of course, nuclear is not problem-free. The biggest problem with it is that it takes years to build. This may be why the World Bank is focusing on extending the life of existing infrastructure rather than funding the construction of new power plants. The UK is a case in point: it has two nuclear projects in progress, both are in massive cost overruns, and the one that is actually under construction has been experiencing a string of delays and, per the latest update, should be up and running by 2029. The other problem: construction emissions.

Yet if the World Bank is lifting its ban on nuclear and climate-conscious governments are throwing their weight behind the atom, then these emissions could probably be overlooked. After all, some situations call for certain sacrifices, and the situation of having an increasingly electricity hungry population is definitely of the kind that could use a sacrifice of a few tons of CO2 to build the power plants that can supply that electricity.

https://oilprice.com/Alternative-Energy/Nuclear-Power/The-Global-Nuclear-Revival-Has-Officially-Begun.amp.html