Nowhere in the world is as critical for the clean energy transition as Asia, which accounts for almost half of global energy demand and is today the world’s highest emitting region, overtaking historical heavy emitters in North America and Europe. Despite economic challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries in the Asia-Pacific region continued to witness record-breaking growth in renewables since 2020.

Now it’s important that mammoth economies and smaller countries alike continue to ramp up renewable energy to meet targets, cut emissions and keep communities healthy. So how can Asian countries achieve a successful clean energy transition?

Here, we look at five examples across the continent: the huge, emerging economies of China, India, and Indonesia; Vietnam, which has had higher-than-expected success on renewables; and Bangladesh, one of many smaller Asian countries which can take lessons from regional leaders to green its own grid. Together, these countries are home to about 43% of the global population and make up over 35% of the world’s energy consumption.

China

In September 2020, China announced its intent to become carbon neutral by 2060, a major follow-up to its previous commitment to peak carbon emissions by 2030. One year later, the world’s second largest economy also came out with a pledge to stop building coal projects overseas, though the details are still unclear. There has been reassuring progress on the domestic front: wind installations reached an all-time high of 72.4 gigawatts (GW) in 2020, an almost threefold increase from 2019. Meanwhile, solar trailed not far behind with 49.3 GW, more than a 60% increase from the previous year.

China’s annual wind and solar capacity additions. Source: China Electricity Statistical Yearbook. View on WRI.org for interactive chart.

Nonetheless, coal continues to come online and remains China’s predominant source of energy at 49% of capacity, compared with 24% for wind and solar combined. To meet its emissions-reduction targets, China must follow through with national plans to begin the phase-down of coal by mid-decade. And while continued renewables growth is expected, seismic shifts in the investment landscape are all but guaranteed given the recent phase-out of long-term subsidies as well as the expected growth in the need for grid upgrades and energy storage deployment.

New policies promise to, at least partially, make up for the subsidy phase-out. Since 2019, China has implemented Renewable Portfolio Standards, which require grid operators, power companies, and some large customers to source a minimum percentage of their electricity from renewables. Additionally, a national carbon-trading scheme began in early 2021, which was followed by a green power trading pilot program in 17 provinces. While the short-term impact of these projects will be small and reporting accuracy concerns remain, carbon and green power trading will be valuable long-term tools for reducing emissions and encouraging the scale-up of clean energy.

India

In November 2021, India pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070. While there is a 20-year gap between the government’s timeline and the scientific consensus on the need to achieve net-zero by 2050 globally, India is still in the thick of developing its economy and lifting 360 million people out of poverty. India has multiple urgent issues to tackle — energy reliability primary among them. Rural communities still face recurring and prolonged outages, which hinder essential services such as health care and education. Unlike China, where growth in energy demand is expected to stay below 20% over the next two decades, India is on a steep upward trajectory: energy consumption is expected to grow almost 70% between now and 2040. Clean energy deployment will thus be vital for controlling emissions in India, currently the world’s third-largest power consumer.

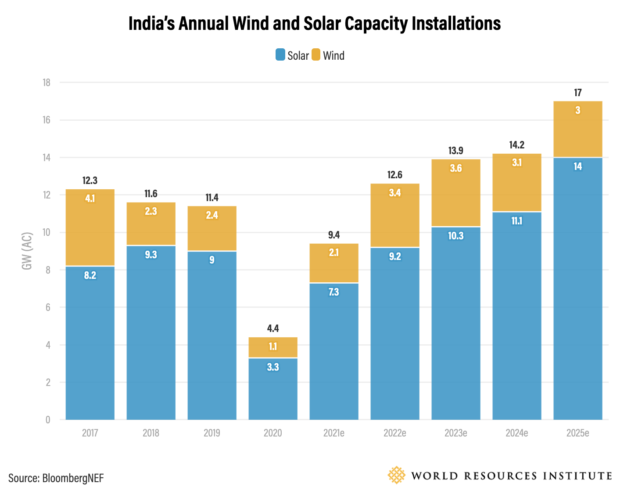

India’s aggressive renewables targets — recently increased to 500 GW by 2030 — have benefited deployment, as have stable government policies such as priority dispatch, which grants market preference to many clean energy plans over fossil fuel ones regardless of price, and a waiver on transmission charges, which gives them a financial leg up over conventional energy sources. These efforts have paid off — clean energy has continuously surpassed coal in new capacity additions since 2017. The country is now set to meet not only its renewables capacity target of 175 GW by 2022 but also its goal of installing 50% non-fossil capacity by 2030.

India’s annual wind and solar capacity installations. Source: BloombergNEF. View on WRI.org for interactive chart.

India also boasts the world’s cheapest solar and second-cheapest onshore wind — currently the nation’s least expensive sources of bulk power generation. Given the variable nature of generation from these resources, investing in storage technologies such as batteries is key to ensuring they meet energy demand at all times. Fortunately, even the combination of battery storage with wind and solar is expected to reach costs lower than those of coal in the coming decade, further solidifying the affordable development case for clean energy in India.

Despite this progress, coal — while in decline — remains the dominant energy source, at 55% of installed capacity. A successful clean energy transition will require an investment of $633 billion over this decade not just in renewables, but also in other key sectors including energy storage, grid infrastructure and demand-side measures such as energy efficiency. These are necessary steps if India is to keep its long-term climate goals in sight, though it cannot (and indeed has made clear it will not) do so alone. If the country is to rise to the challenge, investors as well as high-income nations must step up their commitments to finance India’s efforts.

Indonesia

As in India, Southeast Asia’s energy demand is set to grow at breakneck speed — almost 60% between now and 2040. Indonesia, the region’s largest economy by far, will drive much of this growth. The good news is that Indonesia vowed at COP26 to phase out coal by the 2040s (conditional on receiving additional international assistance), building on a previous pledge to become net-zero by 2060. The bad news is that the country is still a long way from that reality, with fossil fuels comprising 87% of capacity.

But Indonesia also has the advantage of sitting atop the Pacific Ring of Fire, a region densely packed with tectonic and volcanic activity. This gives the island nation the world’s greatest geothermal potential, with the resource making up almost half (46%) of installed renewables. Solar and wind combined trail considerably behind at only 5% of the total.

Indonesia’s installed renewable power generation capacity, 2019. Source: BloombergNEF. View on WRI.org for interactive chart.

In late 2020, state utility PLN launched the country’s first Renewable Energy Certificate program, an internationally recognized mechanism for tracking clean energy generation. A must-have for any mature renewable energy market, these certifications will help the utility meet existing demand for clean energy, and incentivize more development. Renewable sources were also universally given “must-run” status by the government, meaning that whenever there is an oversupply of electricity, renewable energy plants must continue to run at full potential — leaving it to fossil fuel plants to reduce their generation hours.

But challenges persist. Indonesian regulations prevent most developers from signing deals directly with customers, and corporate users are prevented from purchasing renewables from sources other than on-site solar. This has posed challenges to large corporate consumers eager to meet their renewable energy targets, including Nike and Coca-Cola who have signed on to a statement of demand for renewable energy. Additionally, developers are often hindered by strict local content requirements — policies requiring companies to use domestically manufactured products. This has been especially detrimental to progress on solar and wind, given their reliance on foreign-made equipment. If Indonesia is to capitalize on renewables and successfully phase out coal, it will first have to address these policy barriers.

Vietnam

Vietnam, another nation that signed on to phase out coal at COP26, made an additional commitment to become net-zero by 2050 — contingent, as in Indonesia’s case, on international support. As a medium-sized economy, Vietnam has already made astonishing progress on clean energy, even compared to larger countries. Many of the top markets for renewable energy investment plummeted in 2020, but Vietnam stood out with an 89% increase — the third largest globally. Over the next few years, the country is projected to add almost three times more renewables than the four other major renewable energy markets in Southeast Asia combined.

Cumulative additional renewable capacity forecast in selected Southeast Asian countries, 2020–23. Source: BloombergNEF. View on WRI.org for interactive chart.

Rooftop solar grew from 0.38 GW in 2019 to 9.3 GW in 2020 — an increase of 25 times — mostly thanks to demand from commercial and industrial consumers. Credited to an incentive expiring at the end of the year, the unprecedented boom put Vietnam almost 10 times ahead of its original rooftop solar target for 2025 and placed the country among the year’s top three solar markets in the world, after only China and the United States — a remarkable feat for an economy less than 2% the size of either of its fellow front-runners.

But this growth means there is now more clean energy than the grid can accommodate. Needed upgrades, combined with diminished government incentives, make a slowdown all-but-certain. And despite recent strides, the government’s latest Power Development Plan projects a continued 60% share of fossil fuels in the grid throughout the coming decades. Given projected energy demand, this means that Vietnam may double coal capacity and almost quadruple natural gas powered plants by 2030.

If Vietnam is to remain a leader in the energy transition and come anywhere close to meeting its climate targets, the fossil fuel trajectory will have to be reversed. There are promising reforms underway, such as the enabling of direct off-site transactions between industrial consumers and renewable energy generators. The measure, which has received support from companies including H&M, Nike and Target, would allow for the sale of clean energy in much higher volumes — a necessary step for energy-intensive sectors such as textile and apparel to swiftly transition away from fossil fuels. Nonetheless, bolder action — especially with regards to halting fossil fuel development — remains paramount.

Bangladesh

Vietnam’s achievements prove that the energy transition need not be limited to Asia’s largest economies. Smaller nations have an important role to play, especially in places where energy demand is large and poised to increase. Representing only 0.3% of the world’s economy but 3% of the world’s energy consumption, and with energy demand growing almost five times faster than the rest of the globe, Bangladesh is a case in point.

However, unlike its neighbor, Bangladesh has yet to reach the forefront of clean energy action. While the nation has made huge socioeconomic progress over the last few decades, Bangladesh still faces many development challenges: more than 20% of the population still lives below the national poverty line, and rapid urbanization has kept many city dwellers in extreme poverty. Though access to electricity has drastically improved (thanks partly to residential solar), renewables still account for only 3% of the energy mix — far less than Bangladesh’s original goal of 10% by 2020. Land scarcity, delayed project approvals and a dependence on costly imported equipment are just some of the barriers. More importantly though, major government subsidies for coal and gas remain, which distorts market pricing and lowers the competitiveness of renewables.

But as we’ve seen with Vietnam, with the right mix of enabling measures, such as phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and creating new mechanisms for renewable energy purchasing, Bangladesh, too, can lead the way. With support from developed countries and investors, the sea-level nation could make substantial progress towards its November 2021 goal of going 40% renewable by 2040 — and in the process help avoid the devastating effects of climate change, which loom large on its exceptionally vulnerable population.

The Cornerstone of the Energy Transition

Renewable energy continues to break records across Asia, often driven by swelling demand from major consumers in the commercial and industrial sectors which have been increasingly setting targets and collaborating to expand opportunities. However, many challenges remain as governments, energy companies and investors catch up with the new normal — one where low-emissions sources can conceivably make up the majority of global electricity by the end of the decade.

There is no time to waste. With Asia’s energy usage set to almost double by mid-century against the backdrop of rapid climate change, governments in the region must take swift action. We already know that there is high demand for renewables in the region, and there are already proven policies and mechanisms to expand access to renewables purchasing options. With more than 1,000 of the world’s leading corporations — together equal to almost 30% of the world’s GDP — having established climate targets, markets that fail to respond accordingly risk placing themselves at a competitive disadvantage.

Global corporate power purchase agreements (PPAs) – the major purchasing mechanism for off-site renewables – by region as of November 2021. Without breaking policy barriers, Asia risks not meeting the growing demand for clean energy and placing itself at an economic disadvantage. Source: BloombergNEF. View on WRI.org for interactive chart.

But individual Asian governments cannot — and should not have to — tackle this problem alone. All these countries have called for financial and technical aid from high-income nations, who thanks to their earlier growth stand better equipped to tackle the crisis. If Asia is to live up to its pledges, it will need its international peers to step up their own climate finance commitments, which currently stand at an unmet $100 billion per year. The private sector must also contribute its share of the $1 trillion in yearly investments needed over the next two decades in Asia by offering more and better financing for clean energy and grid infrastructure. Energy buyers must continue to make their demand for renewables known, while electric utilities need to put their best foot forward in providing large-scale renewable purchasing options for their customers. And critically, all these stakeholders must take into account the environmental and social issues that will accompany rapid renewable development. Transitioning nearly half the world to clean energy — and ensuring the transition is equitable — will require a global effort, and each of the groups above has a crucial role to play.