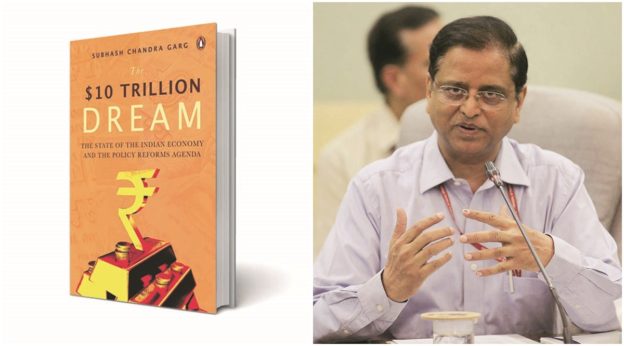

Subhash Chandra Garg, author of The $10 Trillion Dream: The State of the Indian Economy and the Policy Reforms Agenda

Subhash Chandra Garg, the former finance secretary, believes the government needs to get its act together fast on cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology and must strive for a global strategy around it. The Budget’s move to tax income from cryptos will bring some order to the situation but the proposed 1% TDS on payments made on the transfer of digital assets will be difficult to administer, he says. Garg speaks to FE’s Banikinkar Pattanayak ahead of the launch of his book, The $10 Trillion Dream, in which he has offered a raft of policy prescriptions for a wide range of subjects—from expenditure management and taxation to reforms in factors of production—to catapult India onto a high-growth trajectory. Edited excerpts:

On cryptocurrencies

When I headed an inter-ministerial panel on virtual currencies in 2019, our understanding was largely limited to the currency aspect of crypto and the potential of the blockchain technology. (The panel had pitched for a ban on private cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin) Things are much clearer now.

There are three distinct use cases of the crypto blockchain technology: currency; business services like decentralised finance, etc; and asset. The currency case is reflected in two ways—the general currency and the ‘stablecoins’ used for international transactions.

There are unique environments and ways in which the cryptography and blockchain businesses work. First, all the activities take place in what is known as decentralised autonomous organisations. There is no identifiable owner of these businesses (like who owns Bitcoin) even though somebody might have created a particular technology. That makes it tough for authorities to identify the entities or people to tax or regulate or get them registered, etc. So, we need to figure out a way to deal with it.

The second aspect is what we call smart contracts, which are typically self-executing ones that don’t require anybody’s intervention. But our current contract laws don’t have provisions to deal with self-executing contracts.

I think the government needs to figure out the three broad use cases and related technology and bring in appropriate legislative frameworks. It’s quite likely that the government would argue these currencies operate in virtual space and they don’t respect the territorial integrity of any nation. Therefore, there might be a need for a wider set of consultations and agreements across the globe on cryptocurrencies.

The Budget’s provision to tax income from cryptocurrencies brings some sort of order to the situation but it’s limited to the asset use. However, the proposed TDS (tax deducted at source) of 1% on payments made on the transfer of digital assets would be very difficult to administer.

On feasibility of treating crypto as a currency

The currency has to be that of the sovereign; no private entities should be allowed to do so, except, maybe, for the inner use of a platform.

For instance, if you are undertaking a transaction on Ethereum (an open-source blockchain), you might be allowed to do so in Ether (the native cryptocurrency of the Ethereum platform). It’s like many clubs or malls in the country, where we do transactions in tokens offered by them. This is because it would be very difficult in the crypto environment to do transactions in the rupee.

‘Stablecoins’ will find favour with some until the US Federal Reserve comes up with its digital dollar. If the dollar is available in the digital form and transacted as easily as the ‘stablecoins’ are, that would do.

The RBI’s role should be limited to the currency sphere. It’s not suitable for (regulating) either crypto businesses or assets.

On land reforms

We use 75-80% of available land for agriculture and less than 2% for industrialisation and urban planning. The acute scarcity results in land being excessively overpriced. Land prices in Mumbai are among the highest in the world even though we are a developing economy. So, the biggest reform that we need is to increase the supply of land. I have argued in the book that today we have about 140 million hectares of land dedicated to just agriculture. If we limit the use for agricultural purposes to 125 million hectares, given that we are more than self-sufficient in most farm commodities, and free up 15 million hectares for industry, habitation and other urban planning, it will bring about a transformation.

On labour reforms

Mere consolidation of labour laws is no credible reform (The government has consolidated 29 labour laws into four codes). The consolidation actually addresses problems of the 20th century. Times have changed, so have factories. My suggestion is to have just two laws. One should be to regulate hazardous work stations. The other could be for wages where one cost-to-company kind of structure can be considered but don’t regulate it.

On the three contentious, now-repealed farm laws

Of the three laws, only one (the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce) was truly revolutionary, as it could have struck at the root of the Agricultural Produce Market Committees’ (APMCs’) monopoly over wholesale agricultural produce trading. It would also have abolished the system of mandi fees. Both have been hurting farmers for long. While it didn’t propose to dismantle the APMC system, it could have potentially hit their root by luring away farmers. The new law granted freedom to farmers to sell at the regulated APMC mandis or outside. It would have allowed electronic mandis to be set up in a big way.

However, the second law—Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Act, 2020—with its focus on contract farming, was unnecessarily provocative. Mere centralisation of contract agriculture, which is mainly with the states, wouldn’t have made much difference.

The third law—the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act—would have made sense had it repealed the Essential Commodities Act. Why should we have control over storage, price or transportation of farm commodities? Today, we have huge surpluses in many commodities. And where we see a shortfall (in edible oils and pulses, etc), imports should be allowed.

So, the first law was a great piece of legislation, the second one was redundant and the necessary reform in the third one wasn’t proposed. Moreover, the way the laws were brought in was disruptive and states were not consulted.

The way forward is to create an enabling farm law and leave it to states to decide on its implementation, as was done in the case of foreign direct investment in multi-brand retail.

On disinvestment strategy

Given that the government holds just over 50-60% in most of the profitable central public-sector enterprises (CPSEs), outright privatisation with the transfer of management control, rather than minority stake sale, is necessary to boost disinvestment receipts.

Commercially viable and profitable CPSEs suffer today because of the administrative control exercised by the ministries concerned and these are not professionally managed. Many of these CPSEs, including IOC, NTPC, Power Grid, SBI and LIC, are in the energy and financial services sectors.

The government’s holdings in these firms should be transferred to what I propose a sovereign asset management company (AMC), modelled on the pattern of Singapore’s Temasek or GIC. This sovereign AMC can create a lot of value for the assets it manages and the government can get some revenue by selling the share of the sovereign AMC.

Profitable businesses can stay on with the government (in the AMC) as long as necessary. And whenever the assets need to be sold off, the AMC can do it in a very professional manner and the proceeds can come back to the government.

The $10 Trillion Dream: The State of the Indian Economy and the Policy Reforms Agenda

Subhash Chandra Garg

https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/temasek-like-sovereign-amc-could-help-boost-disinvestment-revenues-subhash-chandra-garg/2438859/