The new space economy could generate massive profits — but it could also get in the way of groundbreaking space science.

The first space race was a competition between two governments, each angling to reach space first for prestige and military advantage. Today, there’s a new space race — and in this one, hundreds of private groups are competing for profits.

Between the money to be made from rocket launches, asteroid mining, space manufacturing, tourism, and more, experts predict the global space economy — combining private and public groups — could be generating $1 trillion in revenue annually by 2040, up from about $370 billion in 2020.

Here are some of the players angling for the biggest piece of the pie.

Selling launch services

Until we figure out teleportation, it seems we’re going to continue relying on rockets to get people and goods into space, meaning any sort of plan to make money off-world is going to start on a launchpad.

Not every aerospace company wants to design rockets, but there’s a dedicated group focused on figuring out the most efficient way to reach orbit, and then selling the service to everyone else looking to get off the ground.

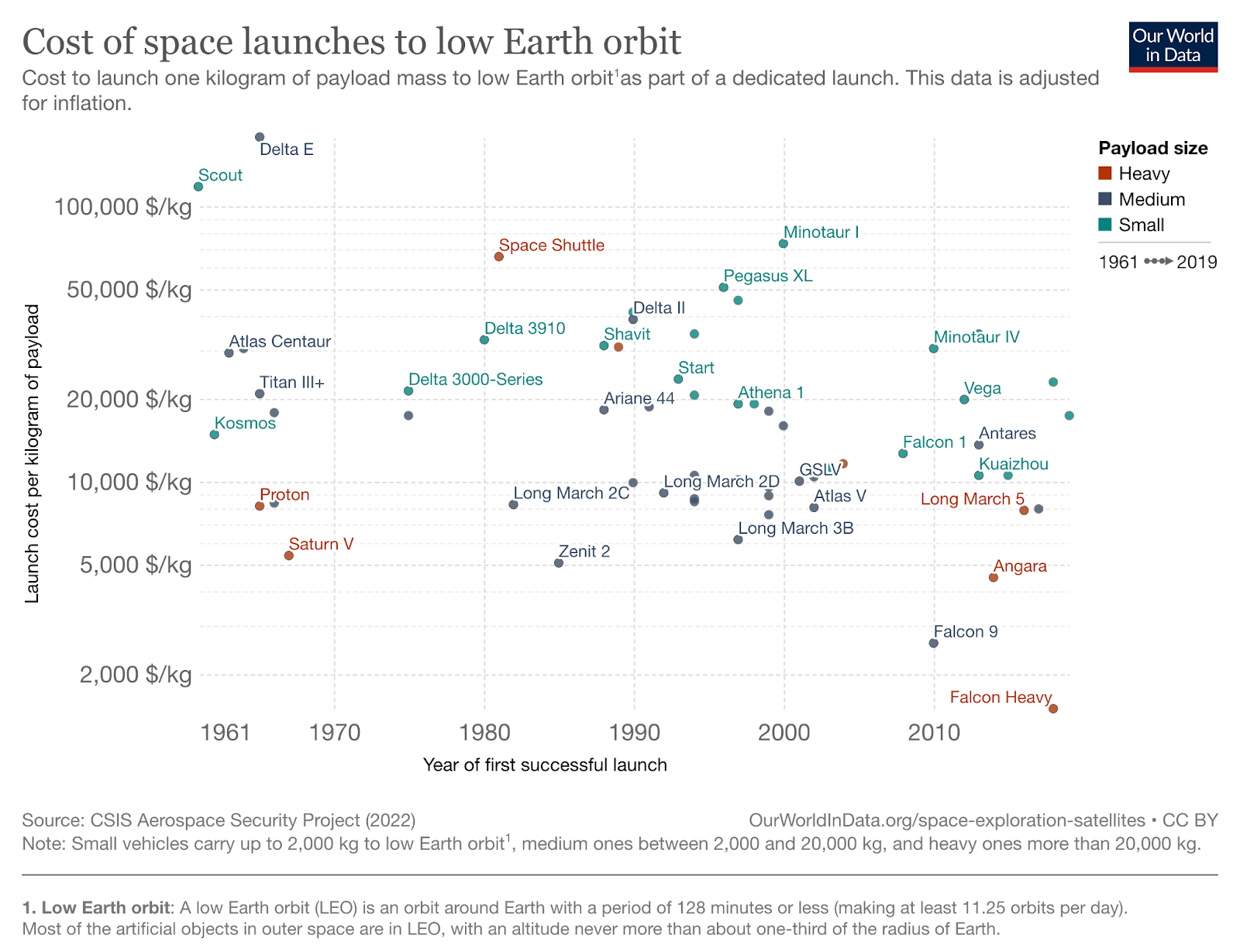

SpaceX is already well-established in this space, thanks to an early focus on reusable rockets to help lower costs. It’s now preparing to launch Starship, the world’s largest reusable rocket — and its enormous scale could slash launch costs even further. While the company’s Falcon 9 costs $62 million to deliver 50,000 pounds to low-Earth orbit (LEO), Starship launches are hoped to cost just $10 million to deliver 300,000 pounds to LEO.

Dozens of startups, meanwhile, are thinking outside the traditional rocket design in the hope their unique rockets will be competitive in the growing launch services market.

Relativity Space just launched the world’s first 3D-printed rocket (though it didn’t quite make it into orbit); SpinLaunch is prototyping a system to literally fling satellites into orbit (though physics might get in its way); and ABL Space Systems is developing a mobile rocket/launchpad combination that would allow it to fly from any flat surface of a customer’s choosing.

“Twenty years ago, space launches were a very government-dominated capability,” Josef Koller, a systems director for the Center for Space Policy and Strategy at The Aerospace Corp, told NBC News in 2022. “Now, there’s much more room to innovate.”

Commodifying Earth’s orbit

While rockets are occasionally used to transport astronauts or send new spacecraft to distant destinations — like asteroids or other planets — the majority are now used to deploy satellites in Earth’s orbit, where they can be used for communication, weather forecasting, space science, and more.

Today, there are about 5,500 active satellites surrounding our planet, but experts predict there will be more than 60,000 by 2030, as falling launch costs make Earth’s orbit more accessible. (Though that’s great for the space economy, it’s not-so-great for astronomy, as the light from thousands of satellites whizzing overhead interferes with telescopes.)

Companies such as SpaceX, Amazon, and OneWeb are building and deploying hundreds of satellites to create global broadband internet networks, while others are focused on manufacturing inexpensive, reliable satellites to carry payloads, such as new camera systems or science experiments, for outside customers.

Still others, such as Varda Space Industries and ThinkOrbital, are developing advanced satellite systems capable of autonomously manufacturing products that benefit from being built in microgravity, such as fiber optic cables, semiconductors, and even biological products and pharmaceuticals.

“We have built a unique way to manipulate chemical systems,” Will Bruey, Varda’s co-founder and CEO, told Bloomberg. “And the most expensive chemical systems on Earth are drugs. We knew that making them in space was the killer app of microgravity.”

Space mining

While some startups hope to build valuable products in space, others see money already there for the taking in the form of mineable resources.

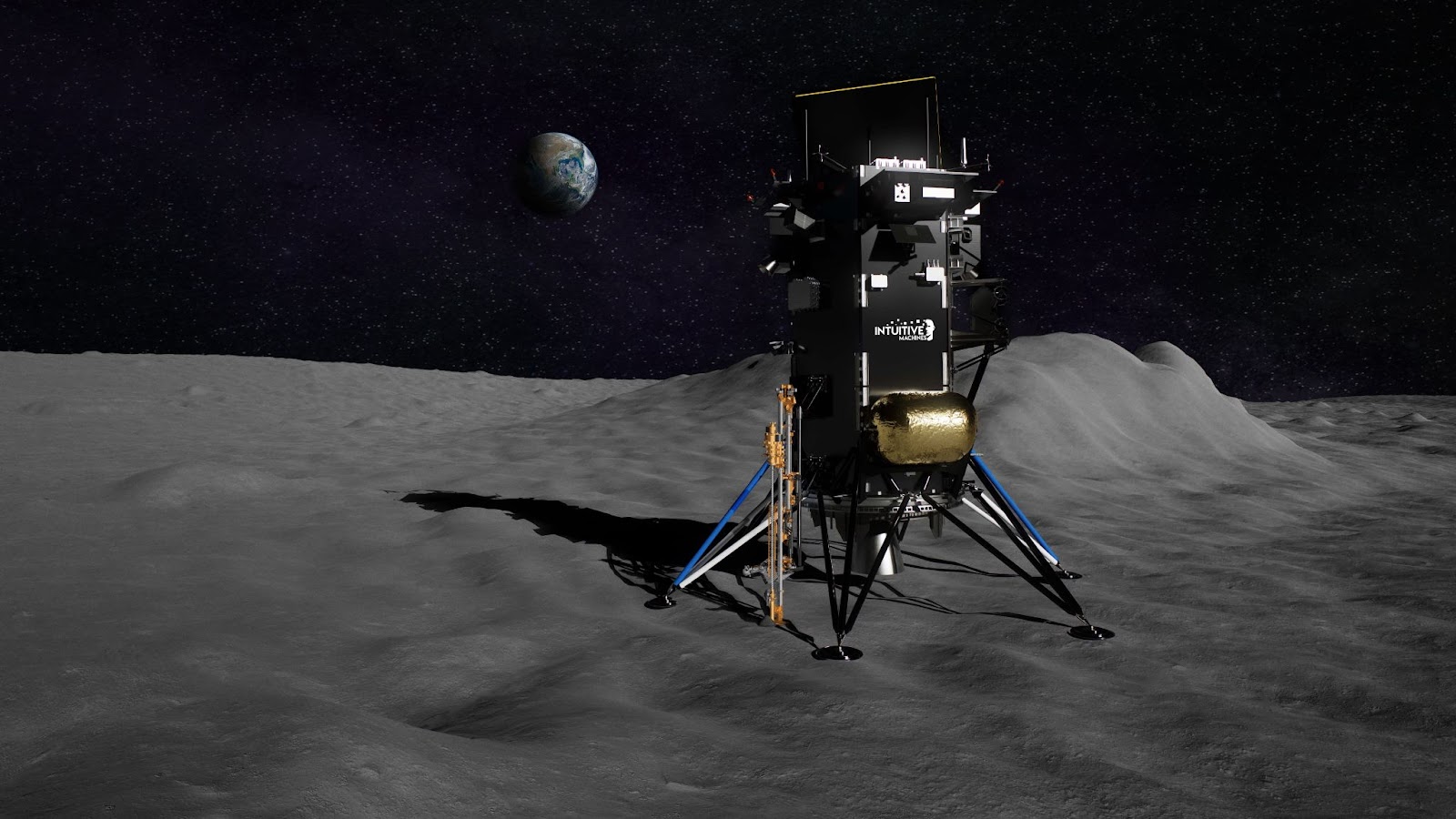

The lowest hanging fruit of space mining is likely the extraction of resources from the moon and Mars that could help support astronauts on long-term missions — this will help cut costs for space agencies as it’ll mean they don’t have to ship all of those supplies from Earth.

NASA is already contracting lunar mining partners, which it hopes will be able to mine metals for off-world construction and extract water for astronauts to drink, grow food with, and even split to produce rocket fuel.

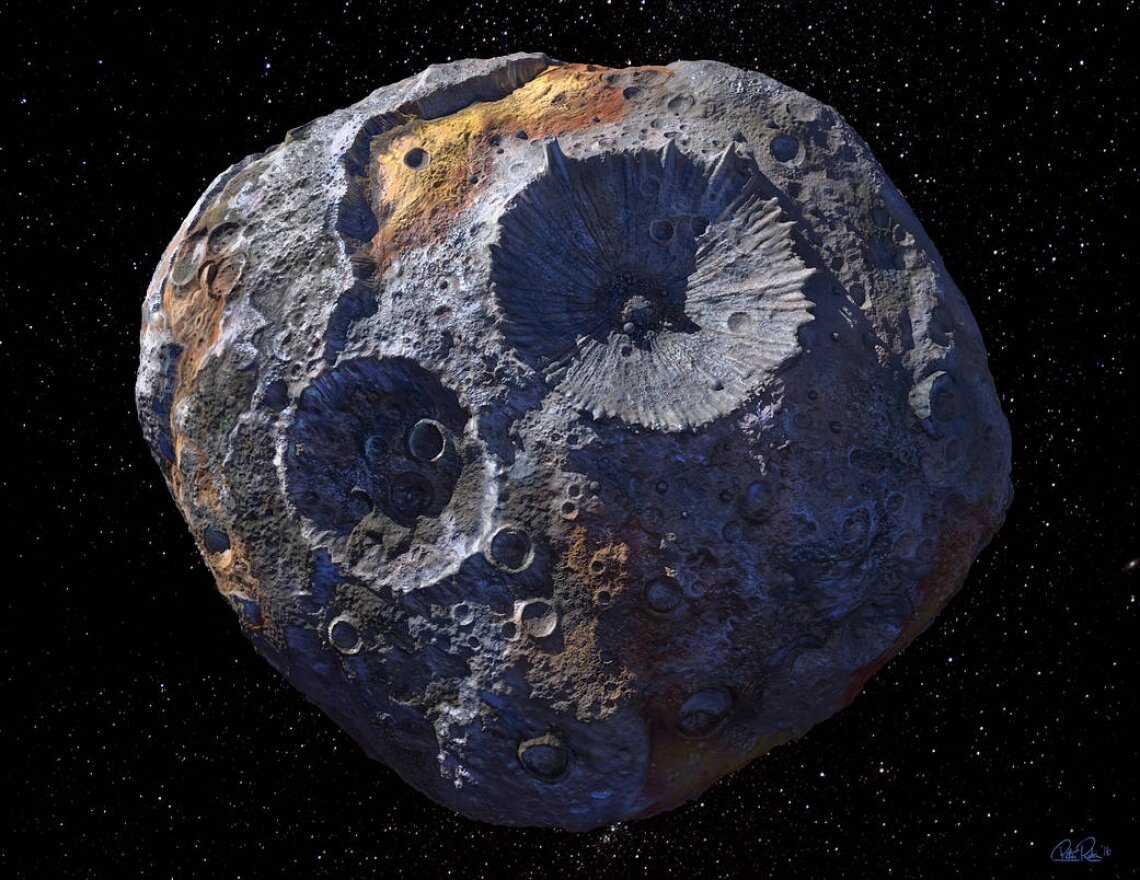

There are also potentially mineable resources on the moon, asteroids, and other space bodies that could be useful — and valuable — here on Earth, including rare metals and minerals to fuel future fusion reactors.

Mining just the 10 most cost-effective asteroids — that is, the ones that are easiest to reach and mine — could theoretically generate $1.5 trillion in profit, according to Asterank, which measures the potential value of NASA-tracked asteroids based on data from the Minor Planet Center and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

While it’s still not clear whether it’s even possible to get these goods out of space rocks and back to Earth (let alone at a cost that’s competitive with terrestrial sources), dozens of companies are trying to make it happen. One of them — Astroforge — plans to actually attempt to land on an asteroid before the end of 2023.

The big picture

While these are three of the biggest potential money-makers in the future space economy, they aren’t the only ones. Other groups are focused on sending tourists to space, building off-world entertainment venues, and even using satellites to create massive advertisements.

Arguably the most important segment of the growing space economy, though, is debris management — also known as “cleaning up space junk.”

Earth’s orbit is already packed with millions of pieces of debris, ranging in size from entire defunct satellites down to pieces of paint that chipped off rockets — and a collision with this space junk can potentially destroy an operational spacecraft and put astronauts’ lives at risk.

These collisions can generate more space junk that makes the orbit even riskier, so taking care of the near-Earth space environment is critical for the long-term health of all space missions.

As we continue to send more and more objects into space, the development and deployment of systems capable of removing whatever is no longer needed will be essential to making sure the growing space economy doesn’t get in the way of groundbreaking space science.

https://www.freethink.com/space/space-economy?amp=1