Onno van den Heuvel is global manager of UNDP’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN). Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das ahead of World Biodiversity Day on 22 May, he discusses how specific economic strategies can help preserve nature:

What is the core of your work?

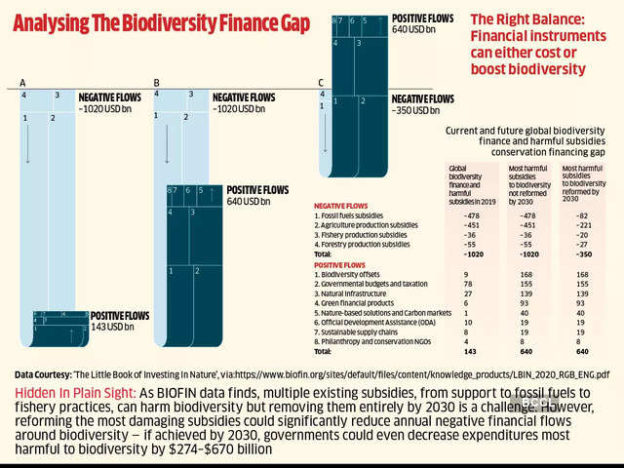

BIOFIN is a network of 41 countries working together to reduce finance gaps in conserving biodiversity. T his multi-step process begins with generating baseline information, such as what the situation with biodiversity funding is in a country, understanding existing mechanisms as well as which strategies could have negative impacts on nature and researching how much a country already spends on biodiversity. We take this baseline data, add how much more finance is needed and highlight the finance gap — we then create a national or sub-national biodiversity finance plan. This includes priority actions for financing selected by national and local stakeholders which they think have the potential to fill the finance gap. This encompasses mechanisms like taxes, subsidies, green bonds, offsets, fintech, etc., which raise money and reduce negative impacts from existing fiscal instruments.

What is the economic value of biodiversity? Why should the private sector protect this?

We don’t even know the full economic value of biodiversity with many species on Earth not having been documented yet. We know only part of the picture but even with that, the total value of ecosystem services, like crop pollination, water purification, carbon sequestration, etc., is estimated to be between $125 to $140 trillion per annum — this is significantly more than global GDP.

The private sector must help protect biodiversity for multiple reasons. There are intrinsic reasons whereby every human has a duty to preserve others from harm — we don’t want to see river dolphins or rhinos go the way of the now-extinct dodo and woolly mammoth. There are legal reasons too — almost all countries have signed up to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). This is now a part of national legislation and commitments. Last December, a new strategy for the next decade was adopted in Montreal which has dedicated targets for the private sector — a very important part is that companies start to measure their impacts, dependencies and risk-related investments in nature to ensure they don’t support practices which harm the environment. The Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) provides a methodology whereby companies can measure the impacts of their investments.

The risk of investing in a loss of nature has been underestimated for a very long time, similar to the processes which caused climate change — this has now led us to the possible breaching of multiple planetary boundaries. The World Economic Forum classifies the loss of nature as one of the top five risks for the global economy today, which is a huge concern for businesses. Also, markets for green, organic and sustainable products are only expanding as customer awareness of environmental damage grows globally. This should also interest many companies.

The World Economic Forum now classifies the loss of nature as one of the top five risks for the global economy — this is a huge concern for businesses which must begin measuring their impacts and dependencies on nature-Onno van den Heuvel

Some posit biodiversity conservation can’t override growth, particularly in developing economies — what is your view?

I think we should stop seeing biodiversity and the economy as two separate entities because they are actually deeply integrated. Biodiversity is more than wildlife and protected areas. Agriculture uses soil whose production rate is driven by its biodiversity which includes worms, bacteria, etc. Consider important sectors like tourism and medicine which are highly dependent on nature as well as urban development which needs trees and plants to clean air, absorb carbon and stave off serious health expenses. Nature and the economy are very closely integrated. We must examine these linkages for each sector now.

Biodiversity and the economy are not separate entities — they are actually very deeply integrated-Onno van den Heuvel

What financial instruments does BIOFIN use to create biodiversity funds?

We have mapped such instruments used globally and put these in the Catalogue of Finance Solutions on our website (www. biofin.org). As an example, there is our work in the Philippines where we helped generate new public budget proposals for 90 protected areas — this raised $40 million in new allocations. In Malaysia, we supported an instrument termed ‘ecological fiscal transfers’. This means the way budgets are allocated to states takes nature into account, including a ‘nature dividend’ in the allocation process — this has generated $180 million. Crowd funding is another innovative mechanism — in Costa Rica, such a campaign for afforestation generated over $1.7 million from the public and private sectors and individuals. In Indonesia, we worked on green bonds, helping to identify investments of about $2.7 million in bird conservation. We’re working on 200 different financial solutions across multiple economies.

What are some of the most important but overlooked financial instruments which could be driving biodiversity loss?

A very common one is the subsidies given to chemical fertilisers worldwide. These aim to improve agricultural productivity — however, they have negative impacts on insects and birds, the water cycle and human health. Land conversion and deforestation also receive subsidies, as do unsustainable fisheries practices. We have found that around $800 billion worth of such nature-damaging subsidies exist globally. Most governments currently don’t review their subsidies for the impacts these have on nature — we need to improve these important screening mechanisms.

https://m.economictimes.com/news/et-evoke/natures-ecosystem-services-generate-up-to-140-trillion-per-annum-significantly-greater-than-global-gdp-onno-van-den-heuvel/amp_articleshow/100336527.cms#appDwnldBanner