India’s rising status in the global economy is assured. Already the most populous nation at 1.4 billion, the population is set to grow by another quarter of a billion by 2050 while wealth will triple over the period. This economic snapshot hints at the scale of the country’s future energy needs.

Last week, I had the honour of joining Prime Minister Narendra Modi for a closed session at the first-ever India Energy Week in Bengaluru, an early event as India assumes the presidency of the G20. PM Modi’s message to the wider conference was powerful in its simplicity. India’s approach to meeting surging energy demand will be dual-pronged: rapid deployment at scale of low-carbon technologies and simultaneous bold steps to increase domestic oil and gas production.

The biggest Indian and international players are gripped by the prospect of billions of dollars of investment opportunities. Can India’s energy future measure up to its prime minister’s vision? I spoke to our experts about the country’s energy ambitions.

Upstream oil and gas – a new beginning?

The OALP-IX licensing round, launched in 2022, opens up much of the deepwater areas that were previously closed to explorers. Alignment from the PM’s office down to the regulator sends a positive signal to prospective investors.

Enhanced fiscal terms make these newly opened basins among the most competitive in the world for a deepwater gas field, based on our modelling. Gas pricing, too, is evolving in a commercial direction. A recent auction for deepwater gas offered buyers a formula that included a linkage to North Asian LNG spot prices.

Some Majors, partnering Indian companies, are eyeing a full gas value-chain opportunity, from potential discoveries to selling into the burgeoning domestic market. To support the investment that will lead to gas and fiscal revenues flowing, the government needs to ensure regulatory and fiscal stability. Nor can bureaucracy be allowed to hinder development, with E&P companies globally seeking to minimise the time from discovery to first production.

Oil – the Achilles’ heel of India’s energy mix

Oil consumption is 5.4 million b/d today and will reach almost 8 million b/d over the next decade, overtaking China as the number one driver of global oil demand growth. Imports, already 88% of consumption, will rise to 95% by 2035.

Much more refining capacity is required. India plans to build 2.7 million b/d of new capacity over the next 10 years, almost half of all net additions globally. Biofuels are a big focus. The aim is 20% bioethanol blended in gasoline from 2025 to reduce crude imports and emissions intensity, a goal that’s easier in a vehicle fleet dominated by two-wheelers. But with more mouths to feed, the food versus fuel debate will intensify. Much depends on the supply of next-generation feedstocks, including cellulosic material, biomass and used cooking oil.

Gas and LNG – India’s price sensitivity exposed

In time India could become one of the Top 5 gas markets. The PM wants a ‘gas-based economy’, increasing the share of gas in the energy mix from 6% today to 15% by 2030.

Any discoveries from deepwater drilling are unlikely to contribute materially by then, so LNG vendors are queuing up to sell more volume. But LNG’s price elasticity was brutally exposed last year, soaring global prices killing demand growth stone dead. Consumers quickly switched to cheaper oil products and coal.

LNG has to be the answer if India is to achieve its 2030 goal, but only if it’s competitively priced. Indian demand will pick up again if, as we predict, global prices moderate after 2025.

Power – coal is still king

As gas has faltered, coal is prospering. India will be a lynchpin of global thermal and metallurgical coal demand through the long term. PM Modi understands that the foundations of strong economic growth will be power and steel output. Coal will do the heavy lifting – we forecast demand for coal from the power and steel sectors will grow at 4% and 5% a year, respectively, over the next decade.

Coal remains dominant in India’s power generation mix and, though declining, still accounts for more than half of total output by 2033. Domestic production provides most of that, reducing import costs and exposure to more volatile international prices.

Renewables – giant ambition stuttering

India already ranks fourth globally in renewable capacity, with solar dominating. But despite 300% growth in installed solar since 2017, total renewable capacity of 120 GW was well short of the 175 GW target for the end of 2022 (excluding hydro). Onshore wind installation continues to lag, and India has no offshore wind projects currently under construction despite over 7,500 km of coastline.

This makes India’s renewables ambitions extremely challenging. Reaching the 450 GW renewables target by 2030 will require over 40 GW of wind and solar capacity to be added annually. That’s more than three times the 12 GW average annual installation of the past five years and requires an investment of US$35 billion a year. Rising utility solar and onshore wind costs are additional short-term complications.

Green hydrogen – targets depend on renewables

India has big plans to develop its green hydrogen potential. These include a US$2.5 billion incentive for green hydrogen production and storage technologies in the recent union budget.

A good start, but current support is insufficient to realise India’s vision of becoming both a leading green hydrogen producer and exporter. Slow renewables roll-out is a problem. India must substantially increase its delivery of wind and solar if it’s to decarbonise its power grid and deliver the estimated 125 GW of renewables needed for its 5 Mt green hydrogen production target by 2030.

A glance at India’s green hydrogen project pipeline suggests investors aren’t leaning in yet – proposed projects account for less than 0.5% of global production by 2030.

With thanks to Parag Goyal (Upstream), Sushant Gupta (Oils), Raghav Mathur (Gas/LNG), Sooraj Narayan (Renewables), Roshna N (Energy Transition), Gavin Thompson (Vice Chair AsiaPac, author of the AsiaPac Buzz) and Prakash Sharma (Energy Transition).

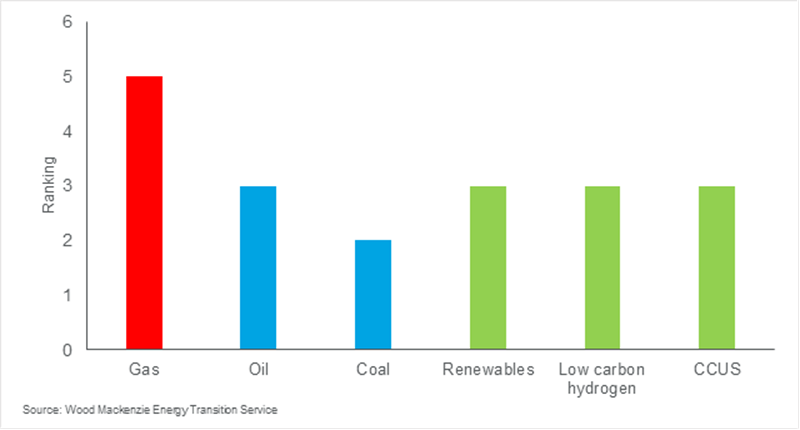

India’s energy mix 2050: Huge investment opportunities in gas and low carbon technologies