IF YOU READ India’s mainstream daily newspapers and scroll through popular news sites, you could be led to believe that the Indian economy is in dire straits, Indian democracy is in serious danger, and media freedom is in deep peril.

The excellent GDP growth figure of 7.2 per cent for 2022-23 enraged many. They scavenged for gremlins that could have infected the data. Ishan Bakshi, writing in The Indian Express, turned a sceptical gaze on fourth quarter (Q4FY23) GDP growth of 6.1 per cent, higher than the consensus estimate.

He wrote: “Another peculiarity of the fourth quarter GDP data is that it points towards the possibility of the country running a current account surplus [or at the very least a minuscule deficit]. A current account surplus would imply weak investment demand in the economy relative to saving. Put differently, instead of borrowing from abroad to finance investments, India was perhaps investing abroad [or borrowing minimally for investments].”

The more plausible reason for a current account surplus in Q4FY23 is the sharp rise in services exports. These totalled nearly $95 billion in January-March 2023, sharply higher than previous quarters. Lower oil prices from discounted Russian crude helped reduce imports. The result: a quarterly current account surplus buoyed by the surge in foreign remittances and foreign direct investment (FDI).

No need to think fearfully, as Bakshi does, that “a current account surplus would imply weak investment demand in the economy relative to savings.” Indeed, other kinetic indicators are positive as well: record passenger car and two-wheeler sales and a surging aviation sector.

In 2014, India was one of the world’s ‘fragile five’, hobbled by high inflation, low GDP growth, policy paralysis, and endemic corruption. India was then the world’s tenth largest economy

When the macroeconomic picture looks bright, dig for bad news elsewhere. Writing in Bloomberg, Andy Mukherjee warned darkly: “A $10 billion push to make semiconductors in India is on shaky ground. Its collapse will expose a major faultline in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s campaign for greater economic self-reliance. Already, influential critics are asking if the much-touted success in becoming a hub for smartphone manufacturing is a hollow claim.”

On cue, Mukherjee turns to former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan for validation: “As Raghuram Rajan showed in a recent paper with two co-authors, instead of ready-made mobile phones, India now imports components. When you add major parts like semiconductors, printed circuit boards, displays, cameras and batteries, the country is a bigger net importer than before.”

In 2014, India was one of the world’s ‘fragile five’, hobbled by high inflation, low GDP growth, policy paralysis, and endemic corruption. India was then the world’s tenth largest economy

But even Mukherjee is forced to admit through gritted teeth: “The Make in India campaign appears to have worked for mobile phones. From being a net importer to the tune of $3.3 billion five years ago, the most-populous nation is now a net exporter. The difference between what it now garners from selling phones to the rest of the world and what it spends on buying them from China is a cool $9.8 billion.”

India’s new Parliament building has meanwhile attracted critics like crops draw locusts. Arguing that India did not need a new Parliament, architect Gautam Bhatia railed in a leading daily: “An impressive colonial structure had been planned and built according to the established norms of a British Council House. Without acrimony or public debate, the project had been entrusted to architect Herbert Baker to design a building appropriate to governing India.”

Note the words: “…appropriate to governing India.” Such nostalgia for a plundering colonial regime?

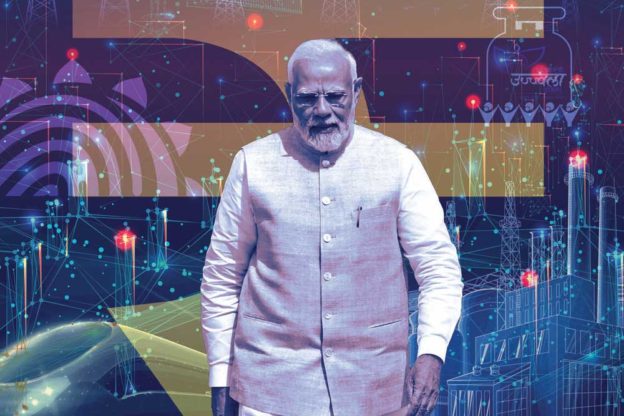

Everyone is entitled to varying opinions but not to varying facts. In 2014, India was one of the world’s “fragile five”, hobbled by high inflation, low GDP growth, policy paralysis, and endemic corruption. India was then the world’s tenth largest economy, behind Britain, France, Italy, Russia and Brazil. In 2023, India is the world’s fifth largest economy and set, at current GDP growth rates, to be the third largest by 2026.

From the fragile five to the first five is an accomplishment, especially given the two lost Covid-19 years and trade dislocations due to the Russia-Ukraine war. Exports, despite these disruptions, recorded the highest ever figure of $775 billion in 2022-23. Merchandise exports were $450 billion; services exports spurted to $325 billion.

What could go wrong? Plenty. But much more could go right. The job of journalism is to report facts accurately. Opinion has a place in op-eds. You can be as biased—or balanced—as you want. The audience will judge you.

What about democracy and media freedom? Foreign observers marvel at the smooth transition of democratic power, most recently in Karnataka. As for media freedom, the tribe of Bakshi, Mukherjee, Bhatia, and hundreds more like them—good, bad or ignorant—will guarantee that.