Brand extensions work well as it is easier for firms to focus on just the new product rather than face the prospect of creating awareness both for the brand and product, as per industry experts.

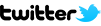

Jeff Bezos, the world’s richest person with a net worth of $187 billion, will travel to space in July as part of the first crewed flight by his space company Blue Origin. Bezos will be flying on New Shepard, the rocket ship made by Blue Origin, which the billionaire founded in the year 2000.

It’s been an extraordinary journey so far for Bezos. In 1994, he created the online bookstore Amazon followed by cloud computing platform Amazon Web Services in 2006. In May, Amazon acquired Hollywood studio MGM, which is home to the iconic James Bond franchise. That’s not all. Amazon today holds a major stake in electric car company Rivian and owns grocery chain Whole Foods Market. In January, Amazon.com also announced the acquisition of podcast startup Wondery, aiming to beef up non-musical content on its Amazon Music app. Then, of course, there is Bezos’s space venture.

Tesla owner Elon Musk is not far behind either when it comes to diversification. Unlike many, in fact, Musk had an exciting 2020—Tesla stocks surged, he had a baby boy and even launched Tesla Tequila. The lightning bolt-shaped bottle, launched in November 2020 in the US, was sold out within hours of lift-off at an eye-watering price of $250 per piece. Interestingly, it all started as a joke. On April Fool’s Day in 2018, Musk had shared a photo on Twitter of himself, holding a sign saying “Bankwupt!”. In subsequent tweets, he said he was “passed out against a Tesla Model 3” surrounded by “Teslaquilla” bottles. It wasn’t long before netizens started asking him to sell ‘Teslaquilla’, which he finally launched last year as Tesla Tequila. As per the brand website, it is “an exclusive, small-batch premium 100% de agave tequila añejo”. Añejo tequilas are typically aged for one-three years in oak—Musk’s was aged for 15 months.

Bezos’s investment strategy and Musk’s branching out from rockets and cars to tequila aren’t the first examples of brand diversification. Many entrepreneurs before them have gone the brand innovation and extension route. It’s easy to see why, as it not only helps establish a brand’s position in new categories, but also benefits the parent brand by creating a greater sense of loyalty, reaffirming the brand promise and consumer perception. It also sustains the parent brand’s relevance in its existing category, say experts.

Growth strategy

Brand extensions work well as it is easier for firms to focus on just the new product rather than face the prospect of creating awareness both for the brand and product, as per industry experts. “It is an effective brand and business growth strategy. But what’s most important is to set up a positive outlook with the consumer regarding the performance of brand/product extensions,” says Mumbai-based Krishna Iyer, executive vice-president of advertising firm MullenLowe Lintas Group. “A strong retail focus based on anticipated consumer demand helps mitigate the risk of failure. Product extensions have seen a fair share of failures, too, and so it requires careful thinking to identify the right categories, as well as the approach to enter those categories. Imagine a brand of condoms called Virgin. It’s a positioning disaster!”

Iyer cites a few examples of brand extensions that worked well in the past. Even though the airline is today grounded, Kingfisher is a good example, he says, as its beer flew off the shelves. Technology giant Google, too, has extended its brand name to most of its products and services. FMCG majors Unilever and Nestle follow a hybrid model of multiple brands with different product extensions. ITC, originally a cigarette company, has extended into categories like hospitality, FMCG and stationery, all unrelated and unimaginable for a brand that started its journey with tobacco. Clearly, extensions need not necessarily be born out of a product. Fratelli, a wine manufacturer, recently diversified into cheese, launching a range of flavours.

Mumbai-based Anjali Malthankar, national strategy director, Tonic Worldwide, a digital-first creative agency, says, “Traditionally, brand extensions were considered to be more successful than new brand launches as these entailed less risk and were also more cost-effective, but times have changed. People have a platform to voice their opinions and we are seeing brands struggle to keep even their equity intact in the trolling world. This reduces the brand’s will to experiment and face scrutiny for new innovations. However, we are noticing brand extensions for local and regional brands, which are low-risk and mostly triggered by needs such as hygiene and cleaning during pandemic.”

Success stories

One of the most innovative examples of brand diversification is the Michelin Star, one of the greatest honours a restaurant can receive. It’s a star rating that is awarded as a sign that a restaurant has succeeded at the highest level. The Michelin Guide, considered the Bible of dining guides, can make or break fine dining establishments around the world. But it is the same Michelin that manufactures tyres.

As per the brand website, Michelin tyre company was established in 1889 by brothers André and Édouard Michelin in France. It was a time when driving was perceived as a novelty, with less than 3,000 cars in all of France. However, the brothers were quick to recognise driving and mobility as a lasting trend. To encourage more road travel—and boost tyre sales—they decided to create a comprehensive guide book for motorists, which would catalogue hotels, restaurants, mechanics and gas stations. In 1900, the very first edition of Michelin Guide was published and 35,000 copies were given out for free. Today, more than 30 million copies have been sold across the globe. It presently rates over 40,000 establishments in more than 25 countries across four continents. “From an image standpoint, it certainly has helped as a halo for a tyre brand. Because tyres, of course, aren’t the sexiest product,” Tony Fouladpour, Michelin North America’s director of corporate public relations, reportedly said.

Other success stories of innovation include Dyson. It revolutionised the category of vacuum cleaners for more than three decades, but in 2019, forayed into desk lamps and other grooming products. Ferrari, whose cars often dominate world racing competitions, successfully ventured into the theme park business with Ferrari World Abu Dhabi in 2010.

However, some brand extensions can dilute the brand. Take, for instance, Callaway, an American global sports equipment brand. It started by making premium golf clubs and later launched footwear, apparel, golf accessories, umbrellas, watches, towels, etc. All products are designed for golfers, but have entirely different engineering and construction methods that can dilute the brand. However, the pluses of brand extension are more than the minuses, opine experts. “For brand and product extensions, the pros far outweigh the cons. In the case of the former, a brand is visible to a wider audience, increasing its equity and loyalty. For the latter, the brand’s new products have a higher chance of acceptance, better trials and increased sales. Extensions are a CFO’s delight, helping companies reduce the cost of new brand development, and optimising distribution, marketing and advertising expenses,” says Iyer.

Then there is Jaquar Group, which started by manufacturing faucets in 1960. Over the years, it included wellness solutions as well—whirlpools, shower panels, steam cabins and spas—and lighting too. “We utilised our expertise, legacy, manufacturing and distribution prowess to foray into the lighting business way back in 2001,” says Sandeep Shukla, head, marketing and communications, global operations, Jaquar Group, adding, “We felt that the gradual move towards LED was the right one. It was a strategic business decision to progress from bath and sanitaryware to lighting solutions, a decision which reaped rich dividends for us as it was a well-researched and insight-based move.”

Pursuing innovation

Brand extensions around the world are created as a result of inspiration and innovation, and today, no sector is left untouched. Take, for instance, gin makers, who have in the past put their brand name on a box of chocolates and even a pair of socks.

Indian companies and sectors are also pursuing innovation and gaining recognition. In 2020, Delhi-based Anand Virmani, founder and CEO, Nao Spirits & Beverages, announced the first brand extension in the form of a limited-edition gin called Juniper Bomb, an extension of another variant called Greater Than. “The restrictions on advertising alcohol have led brands over the last two decades to create brand extensions with the primary motive of using these as surrogates through which to promote the mother brand. Think Bacardi Music CDs or McDowell’s Soda Water. While the result is the same in both cases, the difference is that surrogates are basically empty shells and no one really cares to sell or, for that matter, buys these products,” says Virmani. “An ideal brand extension is one that benefits not just the parent brand, but can also be a self-standing product in its own right. Both should complement each other, with the whole being greater than the sum of its parts,” says Virmani, adding, “Greater Than was the first craft gin in a market that didn’t as yet have a culture for drinking gin. Our aim at that point was to create a solid base for a gin culture. Now, having seen it take hold, we want to build a new level and get gin drinkers to experiment with different flavour profiles.”

If, however, there is no understanding of the core values or brands are just trying to extend into other categories, it will result in failure, say experts. In 2002, soap and detergent major Nirma aimed at alternative growth avenues to reduce its dependence on the stagnating and highly competitive soap and detergent market by test marketing toothpaste and shampoo. It failed. Pond’s, too, suffered a similar fate in its initial years. “After a few hits and misses with toothpaste and deodorants in the early years, Pond’s took off when it focused on skincare and beauty. It used its equity in beauty and skincare, and added gravitas with its premium portfolio by extending the target group,” says Malthankar, who has been part of the brand’s ‘mass-to-class’ journey besides working with other FMCG brands like Clean & Clear, ITC Skincare, Go Air, Jo & Doycare soaps and Ferrero Rocher, among others.

“A brand extension benefitting the parent brand is completely dependent on the success of the extension,” says Malthankar, who is working on a brand that has entered a different category—from vehicle to apparel. “When a brand has a strong purpose and point of view, it makes for a better extension than a brand that is based on the success of a particular product category. Good examples of strong purpose are Reliance, which is known for value, and Tata for trust,” she says, citing examples of some recent Tonic Worldwide projects such as Glucon-D ImmunoVolt (immunity bites for kids), Nutralite Choco Spread (a healthy choco spread) and lingerie brand Enamor’s athleisure wear.

As per Shukla, extending a brand outside its core product category can be beneficial as it helps evaluate a brand’s overall relevance and appeal. “In our experience of shifting gears, it worked to our advantage as the customers of our new product extension (lighting) had values and aspirations that synchronised and matched with our core business… and the core promise of the new product embodied that of the brand. Since Jaquar was already a well-established brand name, it increased consumer interest and willingness to try our new product. Hence, our move was accepted by the market. Extending a brand outside its core product category can be beneficial as it helps evaluate a brand’s overall relevance and appeal. If the brand enjoys great trust and equity, an extension that addresses a need gap in the market can augment the brand’s appeal and business. Having said that, the flip side can’t be ignored too. Brand extensions in unrelated markets may lead to loss of reliability and, if the move goes wrong, the new product may generate implications that can hamper the image of the core/original brand,” he says.

Going ahead what we need, Shukla says, are home-grown cutting-edge ideas. “We have a long way to go. India will truly take the spotlight as a global hub when real innovation takes place on the back of cutting-edge ideas that are home-grown and capable of competing with nations like the US, Germany and Japan,” he says.

An ideal brand extension is one that benefits not just the parent brand, but can also be a self-standing product in its own right. Both should complement each other, with the whole being greater than the sum of its parts — Anand Virmani, founder & CEO, Nao Spirits & Beverages

When a brand has a strong purpose and point of view, it makes for a better extension than a brand that is based on the success of a particular product category — Anjali Malthankar, national strategy director, Tonic Worldwide, a digital-first creative agency

https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/a-new-brand-world-from-amazon-to-tesla-do-brand-and-product-extensions-always-work/2274544/