- Energy policy today is all at once domestic, foreign, climate and security policy. And this will be even more evident in a post-war world.

- There is a historic opportunity for the global energy transition if we can reconcile the security of supply with decarbonization, more renewables and sector coupling technologies.

- I believe four aspects are important to drive our energy transition in a post-war world – and all have to do with innovation.

The Russian war in Ukraine will have severe implications on the shape and pace of the energy transition – not only in Europe but worldwide. We are already seeing shifts in the energy policy triangle, which usually aims to balance security of supply, affordability and sustainability. For now, it seems, security of supply has taken over as priority #1. We shouldn’t, however, make the mistake of losing sight of the other two goals. Instead, we need to ensure that energy does not become a divisive issue within societies. This applies to industrial nations – and it applies to our global community in which 800 million people still do not have access to electricity. We should also be very careful that our climate targets do not fall victim to the war. The latest IPCC report shows that the climate crisis does not take a break. There is no Planet B – this is true for nuclear threats, and it is also true for climate change.

How will the energy transition be shaped in a post-war world?

Although it might sound like a paradox amid the enormous uncertainties, maybe this new era also offers a historic opportunity for the global energy transition. How so? If we manage to reconcile the security of supply with decarbonization, expand renewable energies and sector coupling technologies.

Resilience

To begin with, our economies need to be much better prepared for scenarios where energy supply is disrupted. We need to make our energy systems more resilient. This calls for a thorough analysis of the energy system with attention to strengths and weaknesses, interdependencies and potential threats. It should also answer the question of which priorities an economy must set in the face of energy shortages. Resilience means energy reservoirs must be sufficient enough to balance sudden interruptions in supply. Politics and business must work together to safeguard the energy system against cyberattacks and to increase its cybersecurity in general. That, by the way, is an international task.

Resilience also means that our economies need to diversify supply routes. In the case of pipeline gas, for example, we need to open up other supply routes that allow us to obtain gas from several sources and different suppliers. In addition, liquefied natural gas (LNG) capacity should be expanded in parallel with the diversification of pipeline routes through the rapid construction of new LNG terminals and the commissioning of floating LNG terminals that could be put into operation more quickly.

Win-win partnerships

Another angle we should consider is that green energy partnerships are becoming increasingly important. Some countries can contribute their know-how of energy transition by developing zero-carbon technologies; others have the natural conditions to provide green energy. This is how win-win partnerships need to be created. It is precisely the strength of these partnerships that will matter as we build a global green hydrogen economy.

When it comes to resilience of energy systems, diversity matters: multiple energy suppliers, multiple energy supply routes, multiple fuel sources, and an emphasis on energy efficiency and security. Globalization is not over. But there is a tectonic shift from countries with abundant fossil resources to countries blessed with wind and sun as a source of renewable energy.

We all welcome the fact that our energy systems are becoming increasingly green and hybrid – think of large on- and offshore wind farms (centralized) and photovoltaics (centralized/decentralized). But we need much more speed in implementing new solutions. I am thinking of my home country Germany and the many years it takes to get administrative approval for new projects. Building LNG terminals in Germany as well as expanding wind parks will be a litmus test as to whether we are able to speed up.

While transforming our energy systems, we must also be honest with ourselves: Until renewable energies are available in sufficient quantities, we will need bridge fuels like natural gas for at least one more investment cycle. That is why we should use proven technologies such as highly efficient gas-fired power plants. They can replace coal and reduce emissions by around 50% to two-thirds. These gas turbines should be hydrogen-capable for a future in which they can run on 100% green hydrogen. In other words, investments in gas technology are sustainable and not leading to stranded assets.

I believe that four aspects are important to drive our energy transition in a post-war world – and all have to do with innovation.

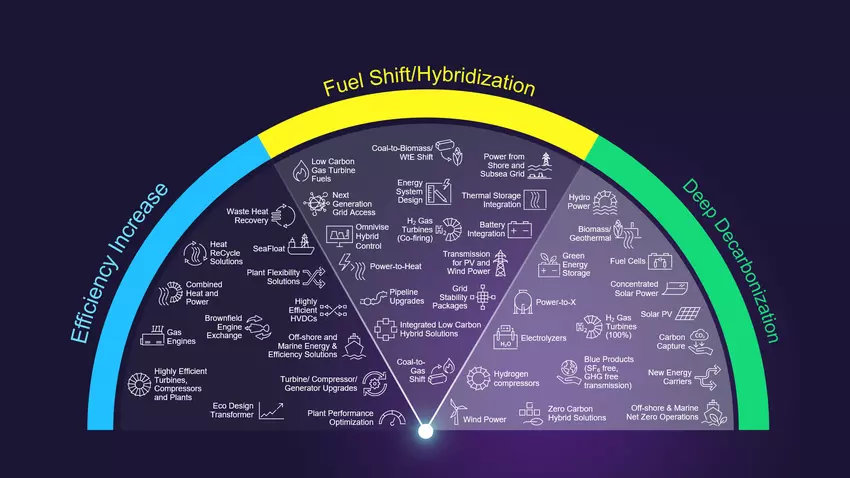

1. Implementing proven solutions that help us move toward net-zero, as well as ending non-sustainable solutions such as coal

2. The upscaling of innovative solutions. Without a well-developed hydrogen economy, the second stage of the energy transition, i.e. decarbonization, will not take off! It is crucial that we increase to industrial scales as fast as possible to significantly reduce the manufacturing costs for hydrogen products. Green hydrogen and its derivatives must be transformed from luxury to commodity products. What is also clear is that we must adapt to higher energy prices and adjust taxation. For a successful market ramp-up and effective sector coupling, the colour of hydrogen should not be decisive in the start-up phase – even green hydrogen has its nuances. What should decide is CO2 intensity and its contribution to decarbonization.

3. We need to be thinking about the holistic energy system. In a few decades, once the share of renewable energy reaches 100% of energy supply, utilities, transmission companies and industry will be able to create a zero-carbon economy. Power plants are becoming hybrid power plants. These include 100% ‘green’ gas turbines that ensure a reliable flow of energy, heat storage, heat pumps for district heating and electrolyzers that produce hydrogen. And since it will be possible to transfer energy to all economic sectors with integrated energy storage systems – be it buildings, mobility, industry, or agriculture – the whole economy would be decarbonized. The biggest challenge then is to ensure the system’s integration capability and resilience.

4. Developing a comprehensive vision of energy for the 21st century. A few thoughts on this: energy policy must secure the future of our planet. In doing so, two aspects are important. First, a comprehensive idea of a “circular economy”. For me, net-zero also means that the wind and solar businesses – which use steel, plastic components, rare earths, and other raw materials – are based on recyclable components. Second, the search for an inexhaustible source of energy. Research decides whether nuclear fusion can be such a source. In any case, the dream of creating an energy source like the sun is alive. And we would do well to continue pursuing such visionary projects – even at the risk of failing.

In many aspects, we are currently seeing how important sustainable, affordable and reliable energy transition is: in the debates about an energy embargo; in an attempt to diversify energy supplies; in becoming net zero. Energy policy today is all at once: domestic, foreign, climate and security policy. This will be even more evident in a post-war world.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/05/energy-transition-in-the-post-war-world/